- Title: Contemplations, The Fractalness of 'Aum Tat Sat'.

- Author: Arvindus.

- Publisher: Arvindus.

- Copyright: Arvindus, 2011, all rights reserved.

- Index: 201107191.

- Edition: html, first edition.

Introduction

It is always challenging to explicate meanings of expressions of an abstract oriented language in a more concrete oriented language. Sanskrit is such an abstract and English is such a more concrete oriented language. Now with Sanskrit being abstract oriented as a whole, it is in its own nevertheless compound of more concrete and more abstract expressions. Of these 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat' are three of the most abstract expressions, with the first being without doubt the uttermost abstract one. These three abstract expressions then are taken together in the highly abstract mantra 'aum tat sat'. It shall be clear that it is no small task to contemplate this Sanskrit mantra with its three components in the English language. Being so difficult to grasp yet at the same time so rich in meaning there is simply no way in which all aspects of this mantra could be elucidated here. Thus shall 'aum tat sat' be contemplated here only from one specific angle. And this is the angle of fractalness. It shall be brought to the fore that the Sanskrit mantra 'aum tat sat' is fractal in nature. The light shed from this angle will of course also fall on certain other aspects of this mantra. These then may in this contemplation be considered to be secondary aspects that in another contemplation might very well have been primary ones.

Fractalness

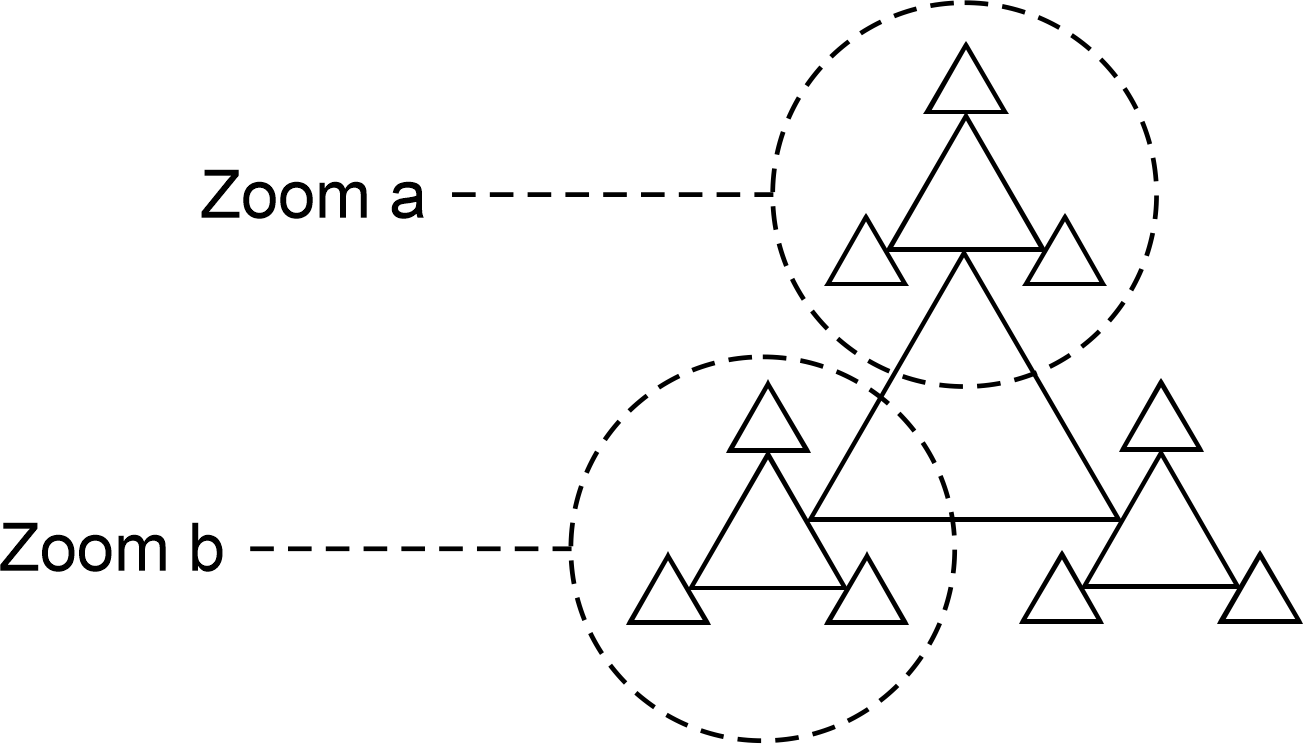

'Fractalness' is a term that is derived from the term 'fractal', which is used in mathematical geometric studies.1 A fractal according to the English dictionary is considered to be "a mathematically conceived curve such that any small part of it, enlarged, has the same statistical character as the original".2 This is a somewhat inadequate definition however, because in its strictness it excludes certain figures that could and perhaps also should be considered to be fractals as well. There are figures for instance that have the same statistical character as the original only in specific parts, while such figures by researchers are still considered to be fractals.3 An illustration of the aforementioned may give more clarity. In figure 1 both the parts in zoom a and in zoom b have the same statistical character as the original. Any part taken in closer look would be similar to the whole. Figure 1 shows thus a strict fractal.

Figure 1.

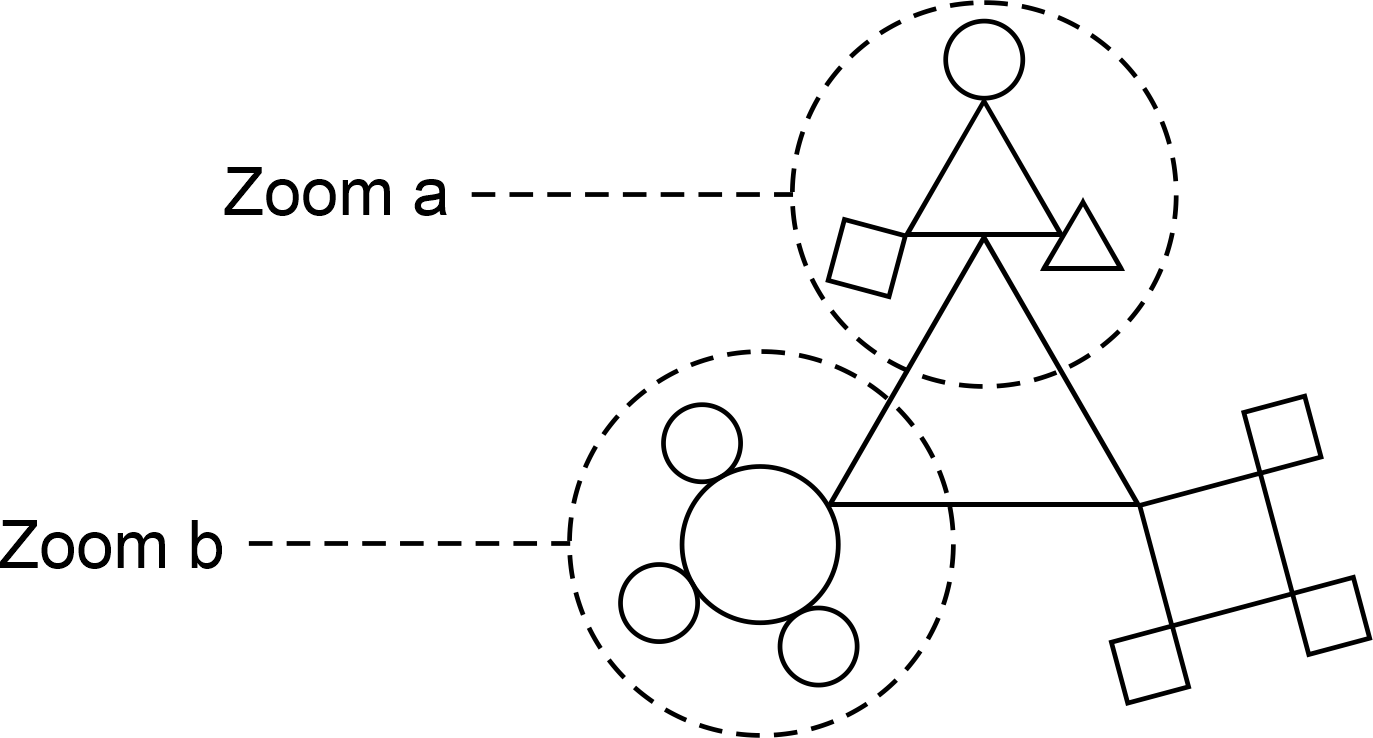

The situation is different in figure 2. There does the part of zoom a have the same statistical character as the original, however the part of zoom b does not have that similarity. Nevertheless do researcher consider figure 2 to show a fractal too because of the so called 'self-similarity' in the part of zoom a. (Considering the term 'self-similarity' questionable in adequacy, shall in this contemplation the safer term 'fractelness' be used to refer to the same idea).

Figure 2.

Taken the above in consideration often a very loose or even no definition is given by researchers, describing instead some of a fractal's main characteristics.4 And the one term which in this context seems to arise in every description is 'self-similarity',5 which in this contemplation is named 'fractelness'. It is this character of fractalness that in this contemplation shall also be sought out in the mantra 'aum tat sat'. And we shall see that the fractalness of this mantra resembles that of figure 2.

Aum Tat Sat

'Aum tat sat' is a mantra or a phrase that is often uttered and written at the end of Hindu recitations and scriptures. It is used especially by the Vedantins (those holding the perspective of non-duality),6 however altered to 'Hari aum tat sat' (with 'Hari' being a name of the god Viṣṇu)7 it has also come in use with Vaishnava's (devotees of Viṣṇu).8 The mantra consists of three words or sounds, being obviously 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat'. We shall have a closer look at these sounds separately, after which they shall be taken back into the whole of the mantra.

Aum

Of the aforementioned three words shall 'aum' be contemplated the most extensively. 'Aum' is in transliterations more often written as 'om' than as 'aum'. Here however we shall contemplate the prāṇava (as the sacred syllable is also called)9 conform Upanisadic (as well as other Hinduistic) considerations. And these think of the prāṇava as consisting of the letters or sounds 'a', 'u' and 'm'.10 Now as said in the introduction is 'aum' without doubt the uttermost abstract Sanskrit expression. It is said that the sandhyā rites (those rites conducted at sunrise, at noon and at sunset)11 merge into the gāyatrī mantra (a major Hindu mantra or hymn, chanted especially at the sandhyā),12 and that the gāyatrī mantra again merges in 'aum'.13 In this way does 'aum' contain the whole of the sandhyā rites in abstract. Therefore do the Vedantic Upaniṣads advice one to meditate on 'aum' as a way to attain Brahman,14 ('Brahman' here referring, or more precisely: 'inferring',15 to the formless god or the non-dual absolute).16 That 'aum' is thought to be a way to realise Brahman becomes clear with the understanding that to the Vedantin 'aum' is the verbal expression of Brahman. And to put it even more strongly; ''aum' is Brahman'.17 'Aum' is Brahman transcendent, and 'aum' is Brahman immanent.18

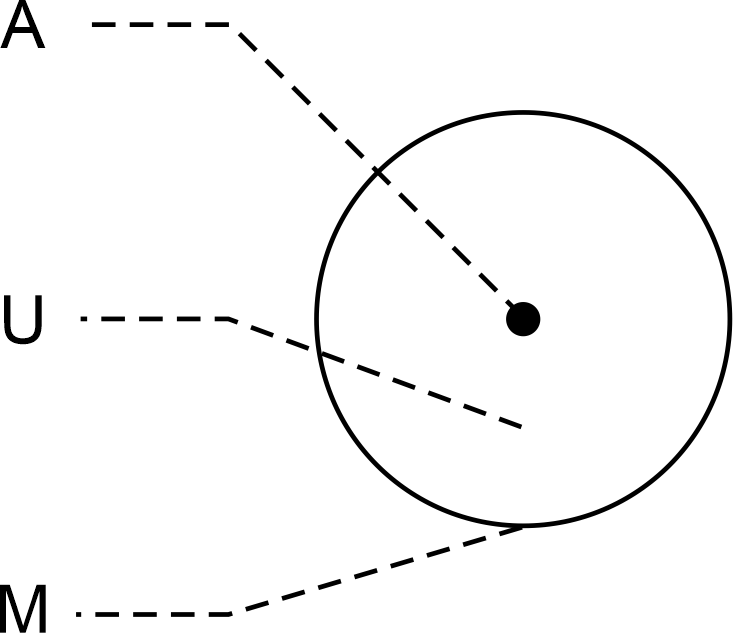

As mentioned does 'aum' consist of the three sounds 'a', 'u' and 'm'. These each have their own significance. These significances shall not be contemplated extensively here, but an entrance to these may be found through the conducted empirical study of phonetics. 'A' as in 'aum' is in that study considered to be the deepest sound, arising from the back of the throat.19 As such is 'a' the sound which is resounded closest to the centre and the heart of a human being. The 'm' as in 'aum' is resounded the furthest away from this centre. It is a nasal bilabial sound.20 With both lips closed and resounding through the nose is 'm' the highest and most peripheral sound. The 'u' as in 'aum' then holds an intermediate position.21 It is resounded between the throat and the nose with both lips half closed. So when the sound 'aum' is resounded does a movement take place from a human's centre to his periphery. Here it should be noted that a Vedantin shall acknowledge the prāṇava to arise indeed from the centre and the heart, because this is considered to be the place where Brahman immanent dwells.22 The 'a' then can be seen as the aspect of spirit in man, the 'm' as the aspect of man's matter, and the 'u' as the intermediate factor. Figure 3 shows the above described idea figured.

Figure 3.

Tat

Of the three words in the mantra 'aum tat sat' is the meaning of 'tat' probably the least difficult to convey in English. For 'tat' is not totally unreasonably translated with the English word 'that'.23 This is a word that shares its roots very likely with its older Sanskrit sibling in the prehistoric Indo-European 'tad'24 (if the root is not to be found in Sankrit itself). The translation is not totally unreasonably because both words are used to refer to a certain external given.25 However the special signification of 'tat' which 'that' lacks is that of an inference to the whole of external things. 'Tat' infers to the outermost periphery of manifestation. 'Tat' in Vedantic thought is considered to be the transcendent Brahman.26 Or differently phrased is 'tat' considered to be Brahman's external aspect.27 With regard to this inference is 'tat' usually translated in English as 'That' with a capital 'T'.

Sat

In contrary to 'tat' does the Sanskrit word or sound 'sat' not have one direct translation to convey somewhat of its main meaning through the English language. Depending on its context it is usually translated with English words such as 'being', 'existence', 'reality' and 'essence'.28 What these English words have in common is that they infer to the most intimate given of any being. Because for sure there is nothing more intimate than one's own being and essence. And what is most intimate is also most immanent (as an etymological contemplation on these two words would acknowledge). So 'sat' infers to the innermost centre of manifestation. Now the innermost centre of manifestation is to the Vedantin also Brahman itself, as we have seen. And this reveals 'sat' then as denoting Brahman's internal aspect.29

Aum Tat Sat

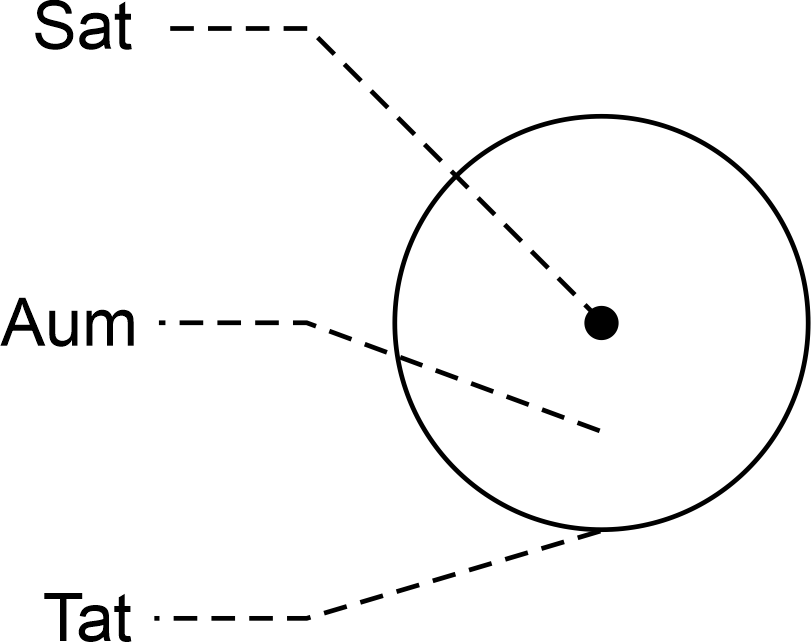

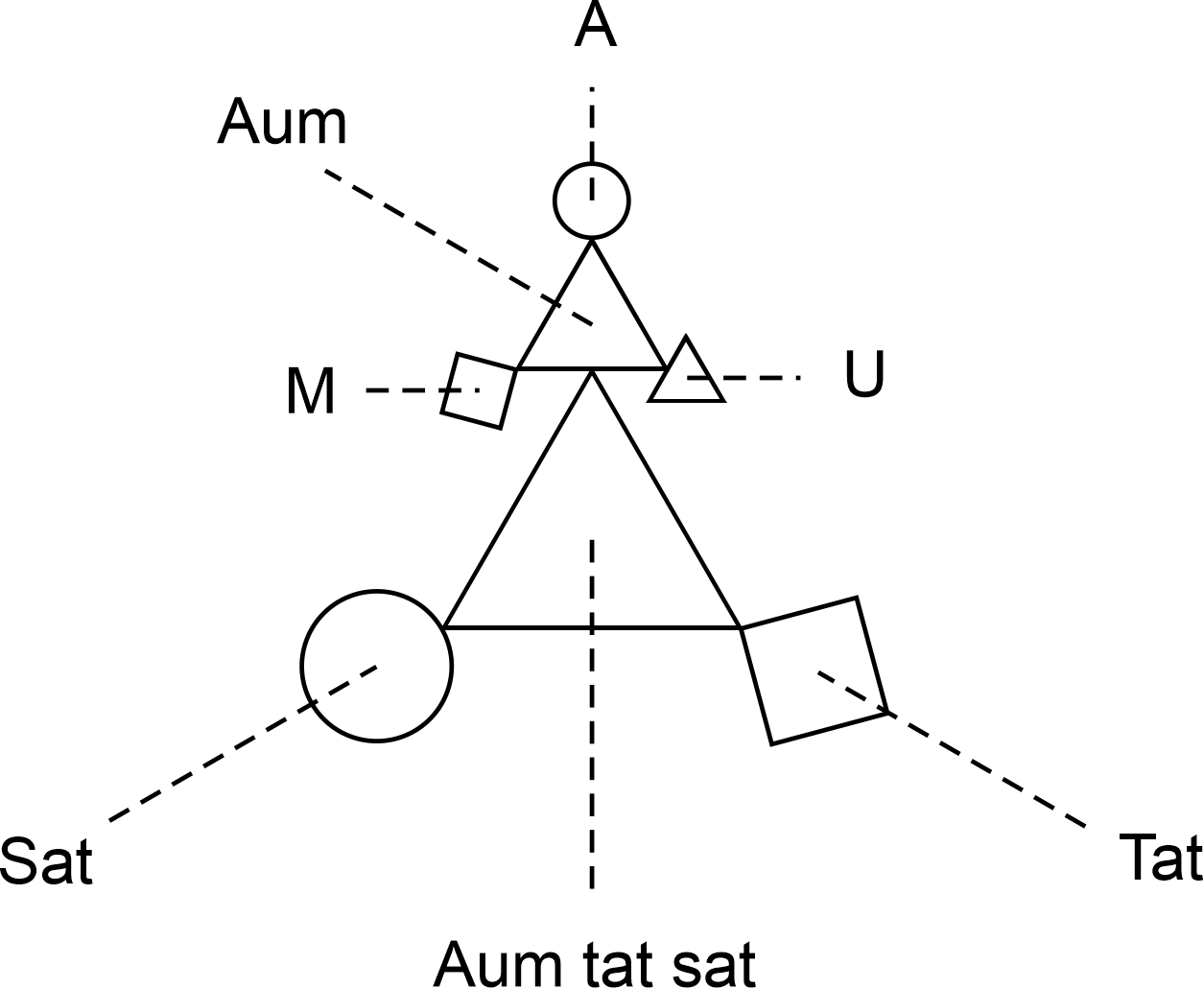

When the three separate meanings of 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat' are taken back into the whole of the mantra 'aum tat sat', and the mantra is figured, then a similar figure arises as the one that arose when 'aum' was contemplated and figured. This time 'sat' is the centre, 'tat' is the periphery and 'aum' is the intermediate factor. That 'aum' itself as a whole takes the role of the intermediate factor can be understood in the consideration that 'aum' as an utterance moves from the centre towards the periphery, stretching itself thus between both. Where 'aum' is the whole with regard to its parts 'a', 'u' and 'm', there is it the intermediate part of 'aum tat sat'. This explicated it is easy to see how the figure of 'aum tat sat' is similar to that of 'aum'. Figure 4 shows an image similar to that of figure 3.

Figure 4.

The Fractalness of 'Aum Tat Sat'

The fractalness of 'aum tat sat' has already come to the fore in the previous paragraph. The figure of 'aum' is similar to that of 'aum tat sat', and with 'aum' being part of 'aum tat sat' a fractalness occurs. The question is how this fractalness can be made visual in a figure. To come to an answer a closer look must be given to the different parts of 'aum tat sat' and their internal relations. These different parts enumerated are 'a', 'u', 'm', 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat' (comprising the whole 'aum tat sat'). Every one of these different parts needs to be figured with a separate symbol, as needs 'aum tat sat' as a whole. However with 'a' and 'sat' both inferring to Brahman immanent, 'u' and 'aum' both inferring to Brahman mediant, and 'm' and 'tat' both inferring to Brahman transcendent, a similar symbol for each of the aforementioned pairs needs to be chosen. And conclusively must the symbol for 'aum' be comprised of the symbols for 'a', 'u' and 'm', just as the symbol for 'aum tat sat' must be comprised of the symbols for 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat'.

Taking the above prescriptions in consideration a figure such as figure 5 may be drawn.

Figure 5.

There Brahman immanent is symbolized with a circle, Brahman mediant with a triangle and Brahman transcendent with a square. The triangle also serves to connect the parts, bringing them into a whole. Thus the triangle symbolizing 'aum' indicates not only 'aum' as inferring Brahman mediant, but also indicates it being comprised of the linked parts 'a', 'u' and 'm'. The same goes for the triangle symbolizing 'aum tat sat', bringing the parts 'aum', 'tat' and 'sat' back into their wholeness. 'A' and 'sat' are both drawn as a circle, indicating them as inferring Brahman immanent. And 'm' and 'tat' are drawn each as a square indicating them as inferring Brahman transcendent.

Now this figure 5 can be recognized as resembling the earlier drawn figure 2. That figure was drawn to show the fractalness of a non-strict fractal. For the figure was attested to be considered by researchers as such a fractal. And thus must figure 5, figuring 'aum tat sat', too be considered to be a fractal. And this consideration then completes the present contemplatlion. 'Aum tat sat' is (a) fractal.

Notes

- Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, (CD-ROM), Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago, 2010, 'fractal'.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0), Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Paul S. Addison, Fractals and Chaos, An Illustrated Course, Institute of Physics, Bristol / Philadelphia, 1997, p. 4.

- Kenneth Falconer, Fractal Geometry, Mathematical Foundations and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester / et alibi, 1990, p. xx.

- Fractals and Chaos, p. 2.

- Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan, Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File, New York, 2007, p. 483.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier, A Survey of Hinduism, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1994, p. 146.

- Steven J. Rosen, Essential Hinduism, Praeger, Westport / London, 2006, p. ix.

- A Survey of Hinduism, p. 78.

- 'Māṇḍūkya Upanisad, in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Swami Gambhirananda (translator), Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008, Ch. 1, sl. 8, or p. 214. "(The letters are): a, u, and m."

- Robin Rinehart, Contemporary Hinduism, Ritual, Culture, and Practise, ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / Oxford, 2004, p. 127.

- Encyclopedia of Hinduism, p. 167.

- Sri Ramakrishna, in: Mahendranath Gupta, Swami Nikhilananda (translator), The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Volume I, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, p. 77. "The sandhyā merges in the Gāyatri, and the Gāyatri merges in Om."

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Praśna Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008, Ch. 5, sl. 7, or p. 478. "The enlightened man attains that (threefold) World through Om alone; and through Om as an aid, he reaches that also which is the Supreme (Reality) that is quiet and beyond old age, death, and fear."

- 'Contemplations, The Absolute Absolute', Index: 201012051, Reference and Inference.

- Sri Ramakrishna, in: The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Volume I, p. 101. "Brahman is beyond vidyā and avidyā, knowledge and ignorance. It is beyond māyā, the illusion of duality."

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Taittirīya Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume One, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008, Part 1, Ch. 8, sl. 1, or p. 274. "Om is Brahman. Om is all this."

- 'Māṇḍūkya Upanisad', sl. 8, or p. 214. "That very Self, considered from the standpoint of the syllable (denoting It) is Om."

- Peter Ladefoged, A Course in Phonetics, Heinle & Heinle, Boston, 2001, first unnumbered page.

- Ibidem.

- Ibidem.

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Muṇḍaka Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008, Muṇḍaka 2, Canto 2, sl. 1, or p. 122. "(It [Brahman] is) effulgent, near at hand, and well known as moving in the heart, and (It is) the great goal."

- A Survey of Hinduism, p. 610.

- John Ayto, Word Origins, The Hidden Histories of English Words from A to Z, A & C Black, London, 2005, p. 503.

- Monier Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymologically and Philologically Arranged, With Special Reference to Greek, Latin, Gothic, German, Anglo-Saxon, and Other Cognate Indo-European Languages, The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1862, p. 360, 'tad'.

- Ibidem.

- Swami Krishnananda, The Philosophy of the Bhagavadgita, (internet edition), The Divine Life Society, Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, p. 110.

- A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, p. 1052.

- Nota 27.

Bibliografie

- 'Contemplations, The Absolute Absolute', Index: 201012051.

- Paul S. Addison, Fractals and Chaos, An Illustrated Course, Institute of Physics, Bristol / Philadelphia, 1997.

- John Ayto, Word Origins, The Hidden Histories of English Words from A to Z, A & C Black, London, 2005.

- Kenneth Falconer, Fractal Geometry, Mathematical Foundations and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester / et alibi, 1990.

- Swami Krishnananda, The Philosophy of the Bhagavadgita, (internet edition), The Divine Life Society, Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh.

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Māṇḍūkya Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008.

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Muṇḍaka Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008.

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Praśna Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume Two, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008.

- Swami Gambhirananda (translator), 'Taittirīya Upanisad', in: Eight Upaniṣads, Volume One, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata 2008.

- Mahendranath Gupta, Swami Nikhilananda (translator), The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, Volume I, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier, A Survey of Hinduism, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1994.

- Peter Ladefoged, A Course in Phonetics, Heinle & Heinle, Boston, 2001.

- Robin Rinehart, Contemporary Hinduism, Ritual, Culture, and Practice, ABC Clio, Santa Barbara / Denver / Oxford, 2004.

- Steven J. Rosen, Essential Hinduism, Praeger, Westport / London, 2006.

- Monier Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymologically and Philologically Arranged, With Special Reference to Greek, Latin, Gothic, German, Anglo-Saxon, and Other Cognate Indo-European Languages, The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1862.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, (CD-ROM), Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago, 2010.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0), Oxford University Press, 2009.